Dressing for success is mostly associated with the bold-shouldered ’80s, but power dressing has been vital for women from the early empires to modern politics.

The term ‘power dressing’ entered our lexicon in the middle of 1970s, when a self-help book called Dress for Success, inspired legions of office workers trying to climb their way up the corporate ladder in skirt suits and sensible heels.

Before long, Dynasty-style dressing, those glitzy and strongly shouldered ‘80s ensembles, became the new world order, when showing your success was a sure-fire way to set yourself up for more.

But now in our more demure times, when distressed jeans and designer sneakers can pass under some boardroom tables, or at least under your laptop during a Skype meeting, dressing for success could seem passé.

Not true. Instead of dismissing the notion of dressing for success, we need to redefine what ‘success’ means to each of us – be it looking presentable in a new-season suit, investing in an it-bag, or being able to work remotely from home in your pyjamas.

As a short history of sartorial statements shows, power dressing is personal, whether the wearer wants to fit into a male-dominated field (read: royal family), or create a new way for women to be perceived on the world stage.

The empress who borrowed from the boys

Like many women who are the first in their chosen fields, the first Chinese sovereign Wu Zetian emulated her male contemporaries. It’s widely believed she wore male imperial robes throughout her reign in circa 600.

Likewise, scholars believe the first female pharaoh in Egypt, Hatshepsut, sat on her throne as other rulers before, bare-chested and with a metal beard (shendyt) and cobra headdress in the 1400s.

As those who love boyfriend shirts or who gravitate towards the men’s section of a fashion store know, androgyny opens up new opportunities to express yourself beyond binary gender boundaries.

Marie Antoinette’s problematic style

The wardrobe of the Queen of any given country during the 18th century was fabricated to display the wealth of their nation – a clever tactic to both attract allies and intimidate foes.

Marie Antoinette, of course, knew how to create a conversation through style, and paid the full price during the French Revolution. However, a point not often noted: it was often the Kings who spent most of the fashion budget, albeit to less uproar, including Louis XVI.

Kate Shepherd style

Just as we see today, commentators can be quick to discredit women in politics, or any position of power, by critiquing their clothing. A remarkable news clipping from the Ohinemuri Gazette in New Zealand in 1896 reads: “Various reasons have been given at different times by men for refusing women the suffrage. Once it was the wearing of the crinoline. No one capable of donning such a senseless garment was worthy of a vote. Then the chignon became the disability. It proved a lack of the necessary wisdom.”

For such a hot-button issue, Kate Shepherd and the suffragists dressed in the sensible yet fashionable dress of the late 1800s. Wearing the tightly fitted bodices and high necklines of the times was a smart, non-threatening tactic, which played to egalitarian values.

Once they won the vote, women wanted to run for parliament and puff sleeves helped them smash through the proverbial glass ceiling. As exaggerated sleeves trend again today, we can’t help but see the correlation between a call to ‘take up space’ in a political landscape and overblown blouse silhouettes.

Le Smoking

In 1966 French couturier Yves Saint Laurent divided the fashion world by presenting the first women’s evening suit. ‘Le Smoking’, as he called it, was a tailored black tuxedo with a satin side stripe, worn at his presentation with a white ruffled shirt.

It was inspired by stars of the 1930s, including Marlene Dietrich, who wore the tuxedo for a powerful and timeless look. However, it was revolutionary to design such a thing specifically for women and it created a culture shock at first – it’s reported early adopters of this style were refused entry by restaurants.

By the 1970s, however, it reached icon status with the support of tastemaker Bianca Jagger, often papped in a YSL suit, and provocative photographer Helmut Newton, who captured some of his most memorable images with models in the revealing suit jacket.

Of the style, Saint Laurent said: “For a woman, Le Smoking is an indispensable garment with which she finds herself continually in fashion, because it is about style, not fashion. Fashions come and go, but style is forever.”

Working girls

John T. Molloy’s best-self-help-seller Dress for Success landed on bookshelves in 1975 and introduced the term ‘power dressing’ to all career hopefuls.

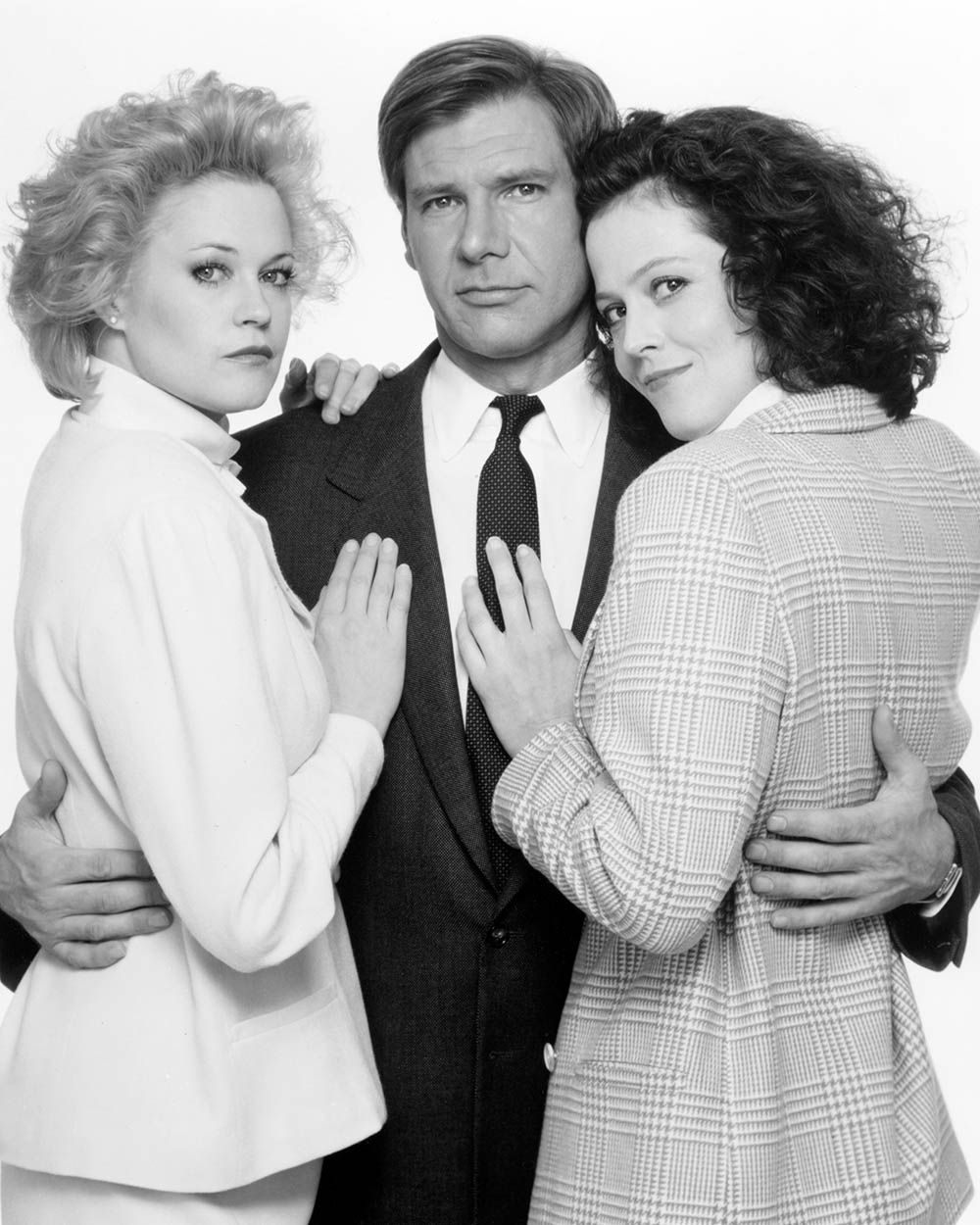

The need to assert yourself with sharp tailoring in striking silhouettes only gained more traction when films such as 1998’s Working Girl featured women who dressed to blend in with their male colleagues, while still standing out from the competition in the office with a hard-working wardrobe.

Helen Clark’s makeover

A presentation skills coach who worked with Helen Clark throughout her career, Maggie Eyre says the former prime minister and administrator of the United National Development Programme had to learn to match substance with style to succeed in a career in politics.

“Working as a presentation skills coach for Helen Clark was a career-defining moment for me and taught me so much about helping women build self-confidence and self-esteem. It was always a privilege,” says Maggie, the author of the new book Being You: How to build your personal brand and confidence.

“What used to irritate me (and still does) is the double standard that exists for men and women,” she continues. “While Helen was in parliament, the media never paid attention to any of the images of any of the senior male politicians and rarely commented on their image and clothing. In comparison, Helen experienced a regular barrage of commentary on her clothes, her hair, her teeth … you name it. But she’s very smart and quickly deduced that the constant criticism about her appearance was distracting.”

Together they went on to develop Helen’s smart, no-nonsense style so she could get on with running the country.

Hillary Clinton’s colour blocking

Power dynamics have always played out most strikingly in politics. Traditionally, women’s political dress codes have favoured royal blue, strong red, and hounds-tooth patterns to show their strength of character.

For women who have been in the game for decades, like Hillary Clinton, a fail-safe solution is the power suit. Her 2016 presidential campaign wardrobe was an exercise in uniform dressing, with suits from American brand Agent in every colour of the rainbow.

While she lost against one very haphazardly dressed man in the end, her suits live on as a symbol of her sheer determination to be taken seriously, and inspired many fashion designers to revisit sherbet-coloured suits still shoppable now.

Jacinda Ardern’s soft power

From the beginning of her election campaign, Jacinda Ardern deliberately chose to wear New Zealand designers including Harman Grubiša, Maaike, Juliette Hogan and Ingrid Starnes, to show her confidence in our local fashion industry. But we see another layer in her fashion message – her wardrobe of softly tailored garments is a way to prove femininity and strength can co-exist.

“Femininity and power are political, many of the women doing interesting things today are still the first to do them in their industries, companies and worlds, and unlike men, women’s clothing is often more alive and varied, different and colourful than the suits that have been so common,” says designer Ingrid Starnes. “Choices about what you wear, who made it, the environmental and physical impact, the labour, all of these things matter. The action of wearing a print designed and made here, these things open up space for the makers and for other women.”

In fact, the Prime Minister has fought for women to have the right to wear whatever they wish since high school. In the 1990s she campaigned for the female students at Morrinsville College to have the option of wearing trousers in the cool winter.

Dress the part

The host of Viceland’s State of Undress TV series Hailey Gates is on a constant quest to work out why we wear what we do.

In an essay for Teen Vogue recently she wrote about the confusion dress codes, or the lack of them, can conjure today.

The silver lining in all of this? “The vagueness of dress codes in our society is, of course, a sign of progress.”