As young girls in the ‘90s, we watched Disney movies where princes saved the day, and fairy tales ended happily ever after. We lip-synced to feminist anthems by the Spice Girls and Destiny’s Child as the ‘Girl Power’ movement took us by storm. Before long the belief that someday we could have it all became ingrained in our psyche. But as we navigate adulthood, our heavily edited fairy tales are unravelling, and the dream we’ve been sold drifts further out of reach. In practice, if we do want it all—both professionally and personally it’s definitely a challenge.

Taking care of busyness

I am no longer inspired by the fact that I have the same number of hours in a day as Beyoncé or that Madonna can thrive on just three to four hours of sleep. Leaving aside the most superhuman or wealthy, I can barely juggle both my career and personal ambitions, a thriving social life, exercise, a tidy apartment, and home-cooked meals straight out of Ottolenghi’s Flavour.

Many of us trying to ‘have it all’ have one thing in common: we are always ‘busy’. But ‘busy’ isn’t the right word for what we’re feeling. ‘Busy’ implies a level of choice, that we’re ‘busying’ ourselves because we want to or because we love the hustle. But often, “busy” hides a darker reality—that we’re overwhelmed, overworked, and burning out.

The personal strain and weariness that comes with living up to the modern-day feminist mantra of having it all has become so common that there’s a term for it: Superwoman Syndrome. Dr Tasneem Bhatia, a trained doctor who is also certified in holistic and integrative medicine met with over 12,000 paitents before writing her book called Superwoman RX. In an inteview with wellness website Well+Good she explains the term: “As women, we want to do it all and play multiple roles,” she says. “But wanting to take on multiple roles can take a lot out of us and more energy than we might [have].”

Technology is partially to blame as smartphones have blurred the boundaries between working and living spaces. Emails continue to flood our inboxes long after the clock strikes 5pm. As the pace of life has increased and technology has allowed us to tick more off the to-do list, our minds and bodies are trying to keep up. And it comes with a price. It’s a phenomenon—coined as ‘Rushing Woman’s Syndrome’ by Dr Libby Weaver—that can dangerously affect our health. As Weaver puts it, our ‘cavewoman-like’ biology can’t respond healthily to the constant pressure of ‘rushing around’.

And what doesn’t help is the constant slew of aspirational—yet unrealistic and highly curated—lives we see on our social media feed. From influencers showing off their daily ‘tap to tidy’ (an Instagram trend where users post a photo of a messy room followed by an image of the same room but tidied up) to our inability to show the raw and authentic moments in favour of heavily filtered highlight reels. It seems there’s a fantasy—and a fallacy—in the image of the ‘super ‘or ‘rushing’ woman. Within each term, there’s the idea that maybe we could have it all if only we dug a little deeper, worked a little harder and used that extra ounce of energy. But in the real world, we can only dig so much. As much as we would like to, we can’t make a 25th hour in the day, an eighth day in the week, or will away the need for a good night’s sleep.

It’s a man’s world

It is debatable whether the glass ceiling has been smashed—or cracked just a little. It’s been well documented that the contraceptive pill has helped to enhance women’s opportunities in the workplace—to plan if, and when, they want to have children. Even though we have that choice, the tiring news headlines remind us of unsurprising statistics and stereotyped outcomes—that women experience more negative outcomes when displaying dominance than men. And recent data from the Ministry of Business, Innovation, and Employment reveals that only one in five of the country’s high growth startups have at least one woman in their founding team.

With recent reports of men ‘discovering’ housework during the pandemic-related lockdowns worldwide, it’s no wonder we are constantly on edge, navigating a world where we’re still expected to do the lion’s share of domestic responsibilities and absorb the burden of emotional labour.

Paying the cost to be the boss

Parenthood is costly, especially for a woman’s career. That cost has been laid bare by two recent studies—one from an economist at the University of Minnesota, the other from sociologists at the University of Massachusetts and NYU—who arrive at virtually the same figures: a six to seven per cent loss of earnings for one child, and another seven per cent loss for the second. While we can certainly strive for a world where that isn’t the case, it is vital to be honest about the real trade-offs women make when starting a family.

Nor is it necessarily an answer for both parents to be working. In The Two-Income Trap: Why Middle-Class Parents Are Going Broke, Elizabeth Warren (then a professor at Harvard, now a United States senator) and her daughter Amelia Warren Tyagi explain: “From the 1970s and onward women increasingly entered the workforce, transforming most middle-class families into two income-households. But with that additional income came additional costs: both parents working meant paying for childcare became a necessity. Plus, the cost of commuting to and from work each day doubled. Other costs outside the family’s control rose, too. The cost of housing as competition to get into the best public-school districts increased, as did the cost of paying—and saving—for rising college tuition. Not only that, but if one parent got laid off, the inherent insurance policy of having an additional potential earner at home ready to step up to get work was now gone, because that other parent was already working, and, again, most of the gain of their additional income was now being gobbled up by these other costs.”

The solutions proposed in The Two-Income Trap—like strengthening the governmental support for families and expanding access to preschool and daycare—make sense for society at large. But they aren’t a remedy for the very real choices women have to make, in the here and now, around balancing their family, professional, and personal lives.

Uplifting indigenous voices

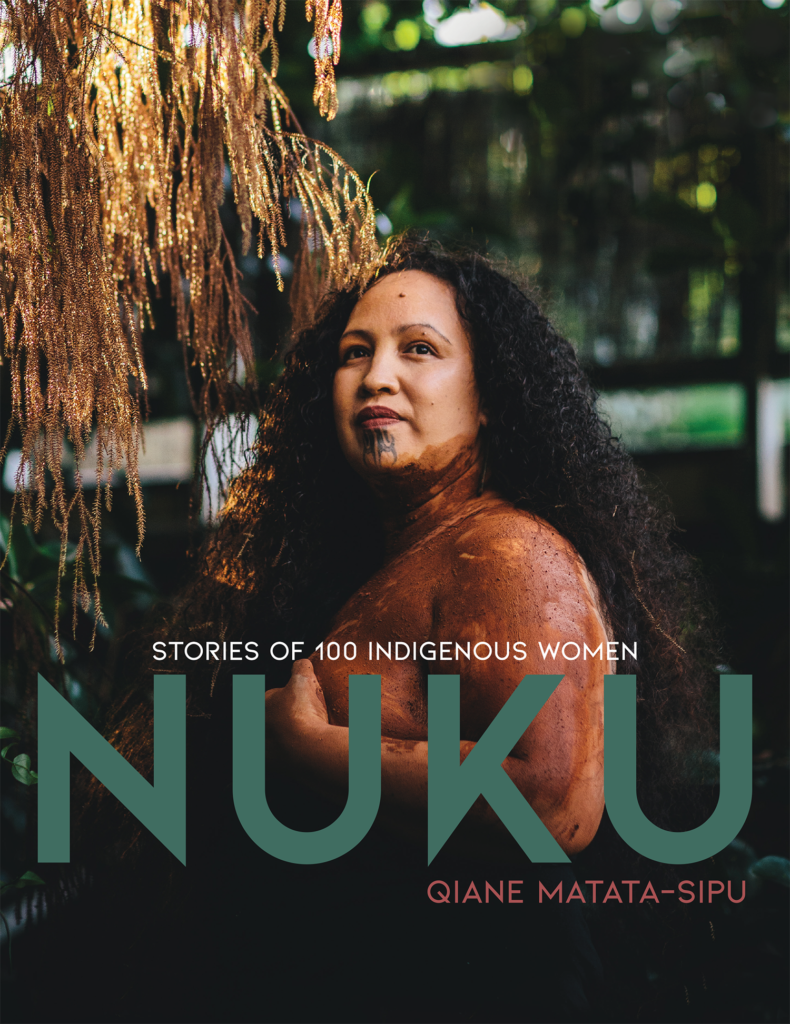

As a female of Indian descent, the more I ‘try to have it all’ in a Eurocentric world, the more I notice myself slipping away from my roots in an attempt to blend in. I speak to Qiane Matata-Sipu, founder of NUKU, a kaupapa or movement that empowers indigenous wāhine to look at the world through a lens made by and for indigenous women.

Matata-Sipu says that today “we live in a world where our cultures have been influenced to become patriarchal”. She explains that traditional Māori culture balances the status of both males and females, as opposed to one over the other, but in a Pakeha world, men are put on a pedestal.

When I ask Matata-Sipu, if women can have it all, she challenges this notion. “Success looks like different things,” she says. “Success isn’t having a career or not having a career—success is being content in who you are.” And while all women come up against challenges, indigenous women face even more. For example, “when we look at the way we are portrayed, we are victims of domestic abuse or statistics of negative social health,” Matata-Sipu says. NUKU aims to smash these perceptions through storytelling, redefining who indigenous women are on their own terms. Matata-Sipu’s upcoming book, NUKU: Stories of 100 Indigenous Women, amplifies the voices of 100 indigenous women doing things differently across Aotearoa—the majority wāhine Māori, and also including Pasifika, Aboriginal, Himalayan and Mexican women.

A new way of doing things

On the surface, most people have a preconceived notion of what it means to have it all. However, success looks different to everyone—and it comes down to individual contentment.

For now, women can be anything, just not everything (and less still, everything to everyone all the time). It’s not quite having it all, and we still have some way to go to smash the glass ceiling, but it’s an answer that might just satisfy that ambitious inner child lip-syncing with her friends and dreaming of the future she’ll make for herself.