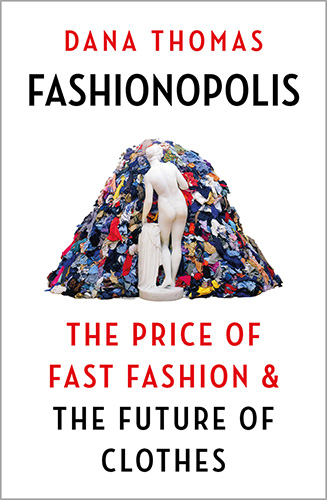

In her latest book Fashionopolis: The Price of Fast Fashion & The Future of Clothes best-selling author and journalist Dana Thomas meets those striving for a more sustainable future, including Stella McCartney.

Over mint tea and cold-press apple juice at a boutique hotel near Stella McCartney’s home in Notting Hill, London, the luxury designer met with Dana Thomas to discuss how she’s moving the needle in ethical fashion.

Known for her use of wool from sustainable New Zealand sheep farms, among many other initiatives, Stella also shared some sage advice for global shoppers who want to help.

Below is the extract from Fashionopolis: The Price of Fast Fashion & The Future of Clothes by Dana Thomas.

“She then showed me her handbag: a honey-hued miniversion of her best-selling Falabella. It was made of synthetic leather and lined with recycled fake suede. As I turned it over in my hands and ran my fingertips across the grain, she asked, “Really, does anyone know it’s not leather?”

Not I, I thought.

In 2006, McCartney’s company turned a profit—five years after its founding and a year ahead of schedule. A “significant” portion of those sales was from accessories, a McCartney spokesman told me; one published report estimated that they make up one-third of her turnover. (McCartney doesn’t reveal such numbers.)

Having proven that going skin-free is a viable business model, she decided to see what other environmentally noxious materials could be eliminated from her line. She hit upon one: polyvinyl chloride, known as PVC.

PVC is one of the most pervasive plastics today. Cling wrap, drinking straws, credit cards, strollers, toys, artificial Christmas trees, Scotch tape, and plumbing pipes are all made of it. In fashion, it is used for transparent shoe heels, vinyl raincoats, synthetic patent leather, and the flexible tubing inside handbag handles. But it is a known carcinogen, and when it biodegrades, it releases poisons into the soil and water table. In 2010, McCartney banned all use of PVC at her company.

“Taking PVC out was a huge thing for us,” she said as she poured a second cup of mint tea. “I’d say: ‘Let’s do a clear heel! Let’s do a Perspex trench!’ PVC, PVC, PVC. ‘Let’s do sequins!’ There are two sequins in the world without PVC. There are millions of gorgeous sequins, but they have PVC.”

By 2016, all Kering brands had stopped using PVC. For McCartney, it was a big win.

Over the years, McCartney has engaged in several independent or joint projects with more affordable apparel companies and advanced her conscious approach to fashion to the mass market— more infiltrating from within. When she designed a capsule collection for H& M in 2005, she insisted on using organic, rather than conventional, cotton. For her long-running col¬laboration with Adidas, she has stipulated no PVC. In 2017, she called on Parley for the Oceans, a marine protection organization that turns plastic ocean waste into thread and yarn, to help make the Adidas by Stella McCartney Parley UltraBOOST X sports shoe.

“Affordability has always been at the forefront of the way I think. At Stella McCartney, we have a lot of entry price points that, for luxury fashion, are not extortionate . . . And if you can’t afford it the first time around, get it in the sale. Get it in the sale of the sale of the sale. Get it secondhand . . . In¬stead of buying five hundred things for X amount”— i.e., fast fashion—“buy fewer things that will last longer”— i.e., better-made, if costlier, fashion. “You will have more value attached to them, you will have more pride at¬tached to them, you will have a better- quality product, and it will serve you well for a long period of time.”

Fashionopolis: The Price Of Fast Fashion & The Future Of Clothes by Dana Thomas. HarperCollins Publishers. $37.99